Kumartuli – From Craft to Culture

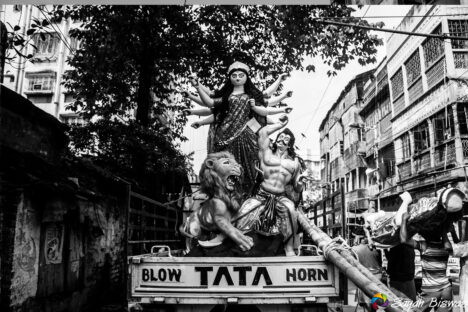

The name ‘Kumartuli’ comes from ‘Kumor,’ which means potter, and ‘tuli,’ meaning locality. Centuries ago, during the colonial era, the British East India Company brought artisans to North Kolkata because of their pottery and clay modeling skills. These craftsmen primarily came from Krishnanagar, Bardhaman, and other rural regions of Bengal, known for their terracotta heritage. In the early 18th century, these potters were given a specific area near Shobhabazar, just north of Chitpur Road, which is now one of the city’s oldest heritage zones. Over time, the potters’ community, which initially focused on making earthenware and household items, evolved into creators of religious idols, particularly Durga, during the annual Sharodotsav. What began as seasonal work transformed into a year-round act of creation, change, and worship. At the center of Kumartuli’s legacy is the idol-making process. This isn’t just sculpture; it is an ongoing act of devotion. Each idol starts as straw tied to a bamboo frame, shaped into a human-like figure. The structure is then coated with layers of alluvial clay from the Ganges, which holds great symbolic meaning. Amid the narrow lanes of North Kolkata, behind walls of crumbling bricks and draped with garlands of bamboo poles, lives a community whose hands have touched the divine. This is Kumartuli, the historic potters’ quarter, where clay is not just dirt; it is a medium of worship, memory, and enduring devotion. Each year, as Bengal prepares to welcome Maa Durga, the artisans of Kumartuli begin their quiet magic — a sacred tradition of forming gods from dust. Their tools are simple: bamboo, straw, clay, and brush. Their hands are instruments of the divine.

But who are these artists? What are their rituals, beliefs, and lifestyles? Let’s take a closer, respectful look into the world of Kumartuli’s master sculptors, the guardians of Bengal’s spiritual artistry. Kumartuli is not just a neighborhood; it is a philosophy. It serves as a living testament to Bengal’s artistic soul and spiritual strength.

The artists of Kumartuli do not seek attention. They are satisfied working behind the scenes. But without them, Durga Puja would lose its essence. Their work reminds us:

* That art can be sacred.

* That legacy matters more than luxury.

* That in the hands of the humble, gods come alive.

The history of Kumartuli spans over two and a half centuries. The name itself comes from “Kumar” (potter) and “Tuli” (a small locality). In the early 18th century, as Kolkata developed under British colonial rule, the Nabakrishna Deb family of Sovabazar popularized the Durga Puja festival among the elite. As the demand for clay idols grew, a community of potters from Krishnanagar, Bardhaman, and Bankura moved to the northern part of the city to be closer to their clients. Over time, these artisans settled permanently in the area that became known as Kumartuli. They started by making clay pots, terracotta pieces, and small idols. Gradually, they became master sculptors, creating larger-than-life Durga idols with stunning precision and grace. Unlike commercial art hubs, Kumartuli was not established for fame or wealth; it was born from necessity, ritual, and devotion. Kumartuli is more than a place. It is a living temple. The artists are more than craftsmen; they are keepers of a timeless promise, translating mythology into matter. In a world rushing towards digital worship and AI-driven creativity, Kumartuli stands quietly, not resisting the future but anchoring it in something older, purer, and more human. In every curve of the goddess’s face, you see a hundred years of patience. In every brushstroke of red sindoor, you feel a mother’s longing. In every immersion of an idol, you witness life’s great truth: all beauty returns to the earth. And when the dhak beats rise again next year, as the city prepares to welcome Durga once more, remember the men and women who bring her to life. The ones who speak to clay as if it were alive. The ones who lose sleep so we can find faith. The ones whose hands will never be seen in the spotlight but have, for centuries, held the very face of the divine.

Some of the oldest traditional families include:

* The Paul family — descendants of Gopeswar Pal.

* The Rudra Paul family — known for maintaining ek-chala (single-frame) idols.

* The Sutradhar community — older caste-based artisans from Midnapore and Howrah who settled in Kumartuli.

Born in the 1890s, Gopeswar Pal was the Kumartuli artist who famously broke tradition. Sidheswar Paul, Gopeswar’s son, carried on the family legacy, preserving the revered ek-chala style while allowing for changing tastes. His strict adherence to tradition kept the studio grounded during times of change. Moni Pal, a cousin, also earned respect by creating idols that blended authenticity with subtle modern touches, greatly contributing to Kumartuli’s reputation. Fourth-generation sculptor Naba Pal continues the family legacy in Bagbazar, with over four decades of Durga idol-making. His grandfather, Jitendranath Pal, created the famous statue in Hirak Rajar Deshe, while Naba studied at the Government College of Art & Craft from 1991, merging classical training with traditional form. Naba and his cousin Amal Pal combine inherited design principles with modern tools, such as revolving stools and patina finishes, to create idols that feel both timeless and contemporary. Brothers Soumen and Amal represent a new generation: art school educated yet rooted in Kumartuli tradition. Mala Pal became Kumartuli’s first widely recognized female idol-maker in the mid-1980s after her father’s passing. China Pal took over her father, Hemanta Pal’s, studio in 1994, preserving the ek-chala tradition despite initial pushback from the male community. Ramesh Pal was among the first to merge traditional Kumartuli skills with formal art training, having studied at the Government College of Art & Craft, Kolkata. His lineage continues through his sons Prashanta and Kamal, who run studios like Shilpa Kendra, producing both clay and fiberglass idols for modern audiences and global markets. Dhananjay Rudra Pal from Faridpur was part of the migrant wave that helped build Kumartuli’s renewed identity. Other sculptors, such as Har Ballab Pal, Gobinda Pal, Mohanbashi Pal, Nepal Pal, and descendants of Rakhal Pal, gradually blended the traditions of East and West Bengal in the area’s craft ecosystem.